Spring 2014Is Health Information Technology Safe?

by Tess Settergren, MHAMA, RN-BC

This article conveys opinions of the author, and does not reflect perspectives of the author’s employer or other affiliates.

Perhaps it is more appropriate to ask: How can we work together to make health information technology (HIT) safer? The Institute of Medicine commissioned a group of industry experts to research and summarize known effects of HIT on patient safety, and make recommendations to the Department of Health & Human Services (HHS) and to other interested parties regarding how to maximize the safety of HIT-assisted care1. Key findings of the 2012 report included identification of a significant dearth of knowledge about HIT effects on patient safety, of the need to view HIT within the larger socio-technical system, and of an imperative for stakeholder collaboration to improve patient safety. Diversity of vendor HIT systems and end-user workflow impacts, inadequate evidence in the literature, and deficient safety reporting mechanisms were identified as factors contributing to the knowledge gap. The report emphasized the wide variance in HIT-related patient harm reporting mechanisms, and recommended a reporting and investigating system for HIT-related deaths, serious injuries, and unsafe conditions. Among the specific recommendations were several calls to action:

- Agency for Healthcare Research & Quality (AHRQ) and the National Library of Medicine (NLM): Expand funding for HIT-related patient safety research

- Office of the National Coordinator for HIT (ONC): Promote safety testing processes for HIT

- Healthcare accrediting organizations: Develop criteria relating to patient safety and HIT

- DHHS: Initiate a HIT Safety Council and a reporting mechanism for HIT-related patient safety issues

Patient Safety Organizations (PSO) formally acknowledge HIT potential safety risks. ECRI Institute, one of the more prominent HHS-listed patient safety organizations5, published their 2014 annual report on the top ten health technology hazards6. Alarm hazards, infusion pump medication errors, and data integrity failures in EMR and other HIT systems were among the top five hazards. Why lump alarm hazards and infusion pump errors with HIT safety? Because the increasing integration of patient care systems is blurring traditional boundaries--medical devices can no longer be considered distinct from electronic health record systems. ECRI further identified the top five HIT safety issues as system interface issues, wrong input, system configuration issues, wrong record retrieved, and software functionality issues. In response to the limitations regarding HIT safety issue reporting, AHRQ created a Common Format for PSOs to collect HIT event data in a standardized way, to enable better analyses that may help to identify prevention and mitigation strategies7.

The ONC published a white paper outlining evaluation of HIT safety concerns8 in the framework of the socio-technical model. The model is comprised of eight HIT domains, each of which must be considered in the context of whole, as well as individually:

- Hardware and software

- Clinical content

- Human-computer interface

- People

- Workflow and communication

- Internal organizational policies, procedures, culture, and environment

- External rules, regulations, and pressures; and

- System measurement and monitoring

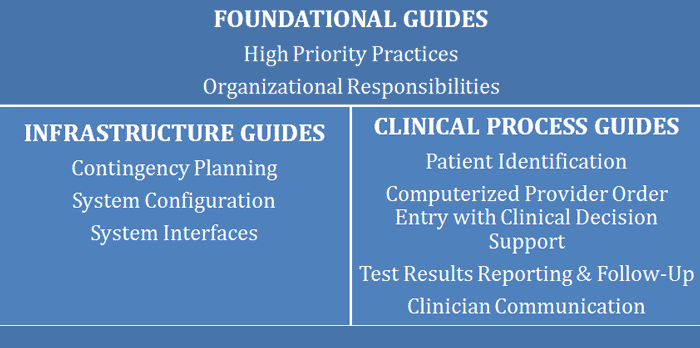

Building on the foundational HIT evaluation white paper, the ONC most recently published a set of SAFER Guides9 to enable organizations to conduct HIT safety self-assessments. The guides are categorized into three functional areas, with the recommendation that organizations start with the Foundational Guides:

/1-JSPS/1%20-%20SoCal%20HIMSS/Old%20Website/Newsletters/Spring%202014/HIT%20Safe_files/Tess-Fig1.png)

Each of the nine SAFER Guides contains a checklist of best practices, based on current evidence, with worksheets intended for comprehensive assessments by multidisciplinary teams. Organizations should use the guides within the context of changes in technology, clinical practice standards, regulations and policy, and associated industry practices to target areas of potential patient safety risk, approaching HIT safety systematically…and continuously. Health IT safety requires a perpetual, closed loop methodology of identifying and analyzing risks, considering mitigation strategies, implementing best practices, and monitoring effectiveness. HIT evaluation is approached in three phases, with corresponding principles, in eight of the nine Guides:

- EHRs and the data or information contained within them are accessible and usable upon demand by authorized individuals.

- Data or information in EHRs is accurate and created appropriately and have not been altered or destroyed in an unauthorized manner.

- Data or information in EHRs is only available or disclosed to authorized persons or processes.

- EHR features and functionality are implemented and used as intended.

- EHR features and functionality are designed and implemented so that they can be used effectively, efficiently, and to the satisfaction of the intended users to minimize the potential for harm. For information in the EHR to be usable, it should be easily accessible, clearly visible, understandable, and organized by relevance to the specific use and type of user.

- As part of ongoing quality assurance and performance improvement, mechanisms are in place to monitor, detect, and report on the safety and safe use of EHRs, and to optimize the use of EHRs to improve quality and safety.

Additional resources for HIT-related patient safety include (not an exhaustive list):

- The EHR Safety Institute: http://www.ehrsafety.com/index.html

- The NIST EHR Usability & Patient Safety Roundtable: http://www.nist.gov/healthcare/usability/ehr-usability-and-patient-safety-roundtable.cfm

- The Joint Commission: http://www.jointcommission.org/hap_2014_npsgs/

- Agency for Healthcare Research & Quality: http://www.ahrq.gov/professionals/quality-patient-safety/patient-safety-resources/index.html

- IOM. (2012). Health IT and patient safety: Building safer systems for better care. National Academies Press: http://www.nap.edu/openbook.php?record_id=13269

- Harrington, L, Kennerly, D, & Johnson, C. (2011). Safety issues related to the electronic medical record (EMR): Synthesis of the literature from the last decade, 2000-2009. Journal of Healthcare Management, 56 (1), 31-43.

- Weiner, JP, Kfuri, R, Chan, K, & Fowles, JB. (2007). ‘e-iatrogenesis’: The most critical unintended consequence of CPOE and other HIT. Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association, 14 (3), 387-388.

- Borycki, EM. (2013). Technology-induced errors: Where do they come from and what can we do about them? Retrieved from http://cshi2013.org/files/Elizabeth%20Borycki.pdf

- AHRQ Listed PSOs: http://www.pso.ahrq.gov/listing/alphalist.htm

- ECRI Institute. (2013). Top 10 health technology hazards for 2014: Executive summary. Retrieved from www.ecri.org/2014hazards

- AHRQ Common Formats. https://www.psoppc.org/psoppc_web/publicpages/commonFormatsOverview

- Office of the National Coordinator for Health IT. (2013). How to identify and address unsafe conditions associated with health IT. Retrieved from http://www.healthit.gov/sites/default/files/how_to_identify_and_address_unsafe_conditions_associated_with_health_it_2013.pdf

- Office of the National Coordinator for Health IT. (2014). SAFER Self Assessment Guides. Retrieved from http://www.healthit.gov/policy-researchers-implementers/safer